Joe Girardi is a good manager. Figure I might as well get that out of the way. He seems to be a dividing force among Yankees fans. You either think he’s in the top 5 managers or in the bottom 5.*

*Yes, I know there are people who think he’s average, but it’s hard to be vocal about averageness, so the extremes, as per usual, pervade.

Here is the thing with Joe Girardi: if you think he’s in the bottom 5 managers, you feel he performed poorly in 2014. If you think he’s in the top 5, you feel he again performed well with a not-so-good roster.

Never one to back down from an unwinnable argument, here is the case for Joe Girardi’s greatness as a manager.

He has little patience for idiocy

After each game, Girardi has no choice but to sit in front of reporters for the postgame press conference. But he doesn’t have to like it, and oftentimes he shows exactly how thrilled he is.

This is obviously a personal thing. I know a few fans who don’t like when Girardi snipes at reporters who ask dumb questions. But I don’t see why. If reporters ask dumb questions, they should get dumb answers.

Yes, I understand that it’s tough to ask fresh, original questions 162 times a year. But it’s also tough to sit up there and listen to the same old, “what were you thinking?” sleep-inducers. Reporters have all game to think about an original question. It’s not that difficult to come up with just one.

So here’s applauding Girardi for, at least sometimes, not tolerating these kinds of questions. He’s no Mike Mussina in that regard — miss that guy — but with Derek Jeter gone at least there will be one guy in the Yankees clubhouse unwilling to constantly tolerate dumb questions.

He manages a quality bullpen

Again, we might find people who contend with the idea that Joe Girardi manages a fine bullpen. They’ll point to instances where he brought in a clearly inferior reliever, when he should have brought in Betances.

On this point, unlike the one above, I won’t concede much. Through the years it has become clear that Girardi puts his relievers in a position to succeed.

What does that mean, exactly?

1) He settles guys into roles. We might decry managers pigeonholing guys into roles like closer, 8th inning, 7th inning. It seems inflexible. But if players feel comfortable knowing they play a specific role, they might perform better.

2) He knows when guys need a break. You can’t keep calling on the same guys day in and day out. Girardi seems to know pretty well when his guys need a breather.

3) At the same time, he remains as aggressive with his usage as is responsible and reasonable.

For the last point, Betances is a great example. Girardi used him as much as possible early in the season, while knowing when to back off before getting him hurt or losing his effectiveness.

Heading into the season it didn’t appear that the Yankees had the strongest bullpen. They’d lost the greatest relief pitcher of all time, and didn’t do much to strengthen it over the off-season (signed Matt Thornton and that’s about it). Even though he needed the bullpen extensively, they still performed relatively well.

He gets the call right

This comes from baseballsavant.com’s replay tool, which is simply awesome. Their other tools are excellent as well.

He outmanages expectations

If a team outperforms its Pythagorean record, is that a reflection of the manager’s work? In isolated incidents, no, there are plenty of factors that can play into a team winning more or fewer games than their run differential indicates. But when it happens year after year, with the manager being the only constant? That’s another story.

In the last two seasons, given a roster that averaged 641.5 runs, against the AL average of 689.5, Giradi managed to beat the team’s negative run differential and win 13 games more than expected. If that happens in one season, maybe it’s a fluke. If it happens two in a row, both with similar conditions of poor offense and a patchwork pitching staff, the manager can start to take at least a little credit.

One question that came to mind: do teams with good pitching and poor offenses naturally out-perform their Pythagorean records in this low run environment? The answer seems to be no.

Tampa Bay, a team that allowed fewer runs than the Yankees, had a higher Pythagorean record than them, yet underperformed that number, winning only 77 vs a projection of 79.

Atlanta, which allowed under 600 runs, outperformed their Pythagorean record by one win.

Miami, which was close to New York with a -29 run differential, underperformed their Pythagorean by a win.

Cincinnati, with a -17 run differential and only 612 runs allowed, underperformed their Pythagorean by three wins.

San Diego is the closest to a team outperforming their Pythagorean in the same way as the Yankees, with plus-two wins.

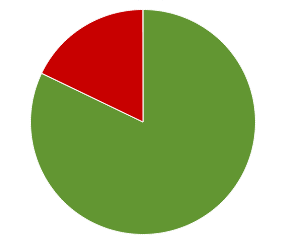

The Yankees were the only team with a negative run differential to finish with a winning record — in both 2013 and 2014. In 2014 only the Cardinals, darlings of the league, outperformed their Pythagorean by as many runs as the Yankees did. No team matched their six wins over expectations in 2013.

Again, this trend (or, phenomenon) can’t be 100 percent credited to the manager. But Girardi does deserve a share of the credit. We know that managers can outperform run expectancy tables. It stands to reason, then, that they can scale that and outperform win expectancy tables.

Love him or hate him, Girardi is under contract for the next three seasons. Given how he’s performed since taking the job in 2008, he’s probably going to last those three seasons.

Guess it’s fortunate that he’s a good manager, eh?